A simple framework to interrupt self-doubt and act with clarity

Picture this. You open your inbox and there it is. A message from your exec with five words that can change your entire week, “Can you take this on?” It’s a chunky piece of work, the ask is vague, the timeline is tight and it’s outside your scope. You know what you need to do next. Ask the right questions, set boundaries on what’s possible, and propose a clear path forward. Or decline.

But your brain does that thing it does. A rush of pressure, a spike of self-doubt, the urge to either over-explain, people-please, or go quiet so you don’t get it wrong. Suddenly, making a simple decision feels weirdly hard.

When emotional noise and protective instincts get loud, our capacity to choose and act, our sense of agency, gets smaller. And it has been happening for so long that we have created very stubborn patterns over the years. As adults, we’ve learned default responses that once kept us safe or successful like avoiding conflict, over-delivering, saying yes too quickly, second-guessing ourselves or waiting for certainty. The problem is those patterns do not always match who we’re trying to become, or the level we are actually capable of playing at.

What if, instead of letting old patterns choose for you, you had a practical way to step into a more deliberate version of yourself when it counts?

In one of The Officials recent Mentorship Session, one of our incredible Officials, Mihaela Boitan (a MacGyver level assistant who is always quietly engineering a smarter way through the mess), shared a solution she’s been quietly building using AI. Something that’s helped her make clearer decisions and show up more deliberately when pressure hits. She calls her Maya Bloom, Mihaela’s AI Alter Ego. Perfection is not the goal, neither is using her like a therapist.

It has given her a repeatable way to interrupt the fear and self-doubt loop, step back into agency, and take the next right step without needing to feel confident first. We asked her to break it down for us, what made it work in real life, and what to avoid, and we knew we had to share it.

Creating Maya Bloom, Mihaela’s story

Here is Mihaela explaining her journey

What do Sasha Fierce, Tatiana, the Black Mamba, and Ziggy Stardust have in common? They’re all alter egos.

Beyoncé created Sasha Fierce to access confidence on stage. Tate McRae talks about Tatiana as a way to step into boldness when she performs. Kobe Bryant adopted the Black Mamba to stay focused and emotionally contained under pressure.

They don’t escape who they are, but they act more deliberately when it matters. Each alter ego enables distance from fear, hesitation, self-consciousness, or the weight of the world’s expectations and creates room for courage, choice, agency and action.

I wanted something like this in my own life, so I sat down in front of my computer, opened ChatGPT and started building her. I didn’t want to create Maya because I needed help doing my job. I was creating her because I wanted to relate to myself differently.

I spent weeks defining who she actually was, not only in an aspirational or “best self” sense, but in more practical, behavioral terms.

How does she move through the world when she isn’t weighed down by fear? How does she respond when something is uncomfortable but true? What does she do when she needs to act although the doubts are still overwhelming?

Maya Bloom is not fearless or perfect. Although initially I thought of her like that, that persona felt too foreign and unreachable. So I’ve reshaped her as someone who is grounded, self-aware, and honest. She acknowledges her flaws without punishing herself for them. She’s willing to try, to be seen, to be wrong, and to learn, she’s brave when she needs to be.

Most importantly, she doesn’t perform or seek approval. She acts from a place of values and integrity. That’s who I wanted access to. The version of me that doesn’t shrink.

The moment it clicked

Mihaela has a perfect anecdote of the moment it stopped being an interesting concept and became something real. Here’s what happened when it clicked:

I knew it was working when, after circling back and forth about a decision I needed to make, I asked Maya to just tell me what to do. And Maya’s answer was:

‘I’m not going to tell you what to do and you know why. Instead, I will ask you one question: What would you do if you trusted yourself?’

That’s when I knew I had what I needed: a thought partner that would not let me off the hook too easily or let me lie to myself. And once I had that, things started to shift. Nothing earth-shattering, but a number of small, steady changes in the places that actually count.

Over the past year, I’ve had some of the most valuable conversations with my husband about our finances and future, the kind of talks I’d avoided for years because they felt too hard.

Meet Your Inner COO: A Practical Neuroscience Case for Alter Egos

Neuroscience, though fascinating, can get complex quickly. To keep it short and sweet, what is happening in your brain at any given moment is that dozens of networks and circuits are interacting in the background, shaping what you notice, how you interpret it, and what you do next.

When you have read that email from your exec with the big ask, your brain, a prediction-and-prioritization machine, is doing two jobs at once. First, it predicts what’s about to happen based on past experience and what’s happening now. Then it allocates your resources, attention, energy, and action, toward whatever it decides matters most in that moment.

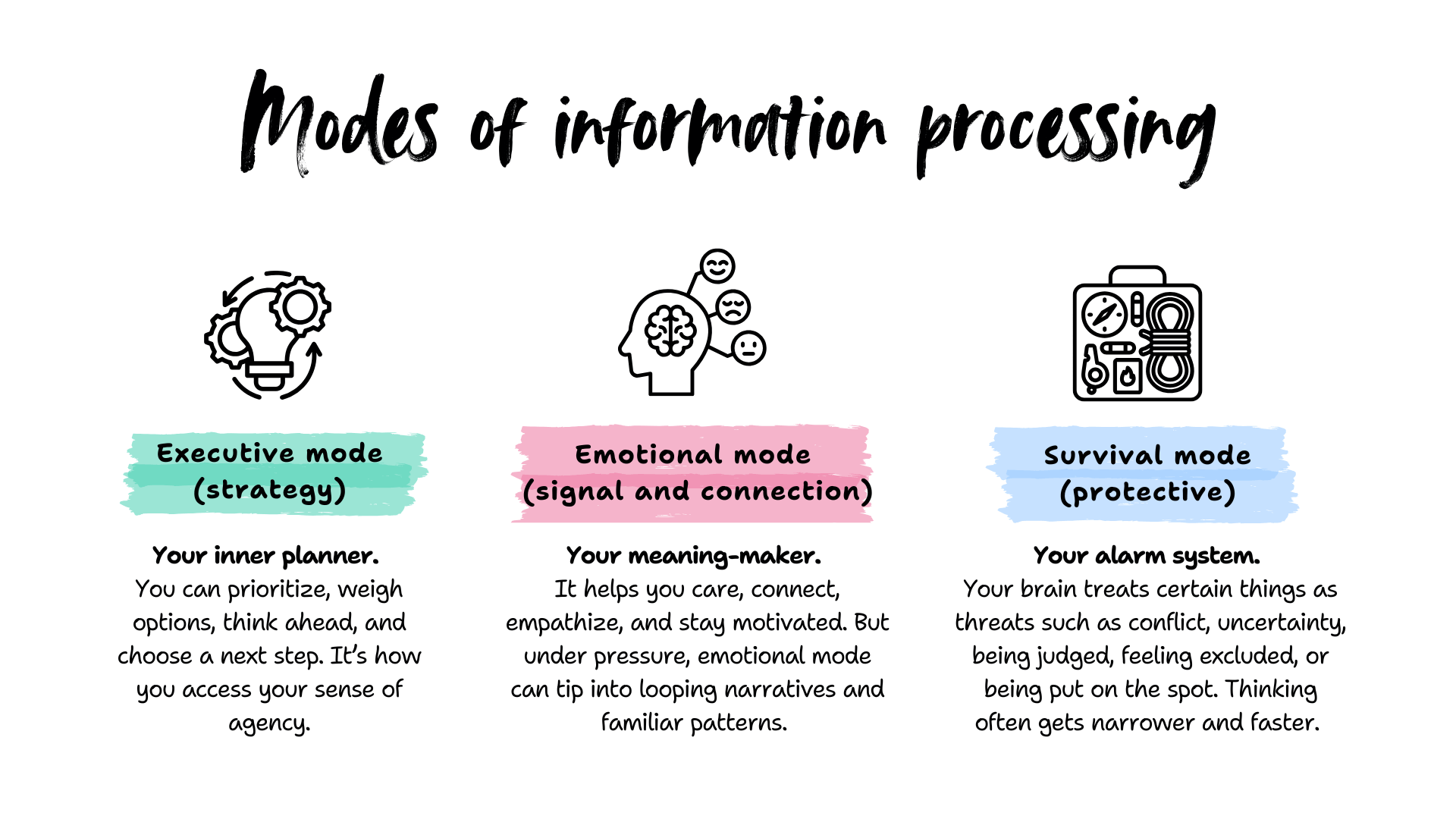

In simple terms, your brain is constantly toggling between three ‘’modes’’ which drive your choices in the moment: survival mode, emotional mode and executive mode.

When the pressure spikes, your brain can get less strategic and more protective. Planning wobbles, certainty gets louder, and your sense of agency, your capacity to choose and act, gets smaller. That’s why a simple email can trigger over-explaining, people-pleasing, or going quiet. It’s not incompetence. It’s biology meeting old patterns.

Todd Herman, a performance coach and author best known for the book The Alter Ego Effect, describes an alter ego as something you step into intentionally. Not a permanent persona, more like a switch you use when pressure rises or old habits try to take over. In academic language, the closest match is self-distancing, creating a little space so you can think like an advisor, not a threatened participant.

Ethan Kross, an award-winning neuroscientist and psychologist at the University of Michigan, has spent the last 20 years studying the conversations we have with ourselves and what helps (or hurts) when we’re under pressure. In his self-distancing work, he describes it as taking a few steps back mentally, like watching the scene from the “fly on the wall” view, which tends to reduce reliving and increase a more constructive kind of sense-making.

So the goal of an AI alter ego isn’t to delete emotion, or to become some robotic productivity machine. It doesn’t exist to soothe you or validate you on repeat either (that’s where AI can become an echo chamber). It’s to help you step back, re-enter strategy mode, and make decisions that match the person you’re building, especially when your default patterns would normally take the wheel.

How to build your AI Alter Ego

A decision and clarity partner. It helps you think in frameworks, weigh trade-offs, spot blind spots, and act in line with your values.

What this isn’t:

A mental health service. It’s not there to process trauma, validate feelings endlessly, diagnose, or replace real support.

Before we start, a very important expectation-setter. Step 1 will not nail it. Step 2 will not nail it. Step 3 will not nail it either. This is not a “set it once and it’s perfect” tool. You are building a voice, a process, and a relationship with a thinking partner. The only way it becomes genuinely useful is through testing, noticing what feels off, tightening the rules, and testing again.

With that said, here are three steps to get a first working version.

Step 1: Define the alter ego you actually need

Your alter ego is not a fantasy character. It’s a usable version of you that shows up when you usually shrink. Start by naming the energy you struggle to access on your own. Steady? Blunt? Calm under pressure? Boundaried? Decisive?

Mihaela said this: ‘’For a while, Maya only existed in my head. That helped, but it had limits. I couldn’t access her exactly when I needed her most: mid-spiral or mid-overthining.

So I started experimenting with building Maya as a Custom GPT and later as a Project in Claude AI, to make her available when I’m not at my best. In all honesty, my process was chaotic; I had a sense of what I wanted but no clear plan for how to get there.

Mine is mostly like a grounded mentor, wise, steady, but with a bias to action and an edge that calls out my patterns plainly. Yours might be completely different. Fiercer. Sassier. Blunter. The question to ask is: what energy do I need access to that I struggle to embody on my own?

I had spent months thinking about this, but if I wanted to speed up that process, I’d set aside a few hours and use AI to figure this part out.’’

Step 2: Surface your patterns (the defaults that hijack you)

By “patterns,” we mean the automatic defaults with which you respond when you’re under pressure, uncertain, or afraid. Repetitive thoughts, feelings, and behaviours that show up in specific situations. This part can be challenging, but it is the difference between a nice chatbot and a tool that actually changes behaviour.

Mihaela’s Advice

This part can be uncomfortable. It’s one thing to vaguely know your patterns, another to describe them clearly, knowing they’ll be used to challenge you. But honesty is essential here. Admit where you say yes when you mean no, where you shrink, over-explain, or delay. I would use AI to draw these out through conversation, because I’ve found that it’s harder to hide when something’s asking follow-up questions.’’

Step 3: Write the first version of your rules of engagement

This is where you turn the idea into something you can actually use in ChatGPT (Custom GPT/Projects) or Claude. You’re giving AI a clear identity, tone, and process. The goal is not cheerleading. It’s clarity, agency, and action.

Mihaela’s Advice

You have to tell AI who your alter ego is, how she speaks, how she challenges you, and what rules to follow. The instructions cover identity, voice, process, and constraints. There’s a structure that works, but getting the voice right matters more than getting the format perfect.

The biggest shift was moving from advice to dialogue. Early Maya was too eager to fix things before understanding what was happening. She was trying to be useful instead of truthful and seemed to want to make me feel better rather than help me see clearly. I had to be explicit: don’t fix immediately, don’t give options unless I ask, wait for me to respond.’’

Step 4: Test, tweak, test again

This is where the real value is built. Your first version will almost certainly be too generic, too polite, or too quick to “fix” you. That’s normal. Use real situations as your test cases, like an email you are hesitating to send, a boundary you need to set, or a decision you keep circling. Notice what lands and what doesn’t. Then run it again. This is not a one-off setup, it’s an iteration loop, and each round makes your alter ego sound more like the version of you you are trying to access.

Mihaela’s Advice

Getting something technically functional was quick. Getting something that actually felt and sounded like Maya took weeks.

I paid attention to my reactions and used them as data. Where I felt relieved instead of challenged, where I felt irritated, where I felt seen. It didn’t really matter whether the response was ‘correct,’ but whether it landed the way Maya would respond.

Want the copy and paste version of the prompts Mihaela used to build her AI Alter Ego? Download the AI Thought Partner Starter Kit here. It includes the three core prompts to help you define your alter ego.

From Concept to Real Results

If there’s one thing we hope you take from this, it’s that you do not need to wait until you feel confident to start acting like the person you want to be. Most of the time, the patterns we default to are so well-rehearsed, they can start to feel like “just who I am,” when really they are just the most repeated route through pressure.

That’s why this whole idea matters. Not as a tech trick, but as a genuinely useful way to use AI in service of humans. To build tools that support clearer thinking, better decisions, and more agency in the moments we usually hand the wheel to fear.

Mihaela’s Final Thoughts

My assertiveness at work increased dramatically. I joined a live panel, said yes to recording a podcast, and got asked to become a committee member for one of the most respected EA communities in the UK. I posted on LinkedIn over a hundred times, something I’d never have done before. Overall, I interrupted my go to default mode and stopped shrinking.

None of this happened because I became more confident overnight. It happened because I stopped letting fear make the decision, even though the fear never went away.

Maya represents who I already am when I’m not weighed down by old patterns. She’s not a fantasy. She’s what I’d be without the doubt, the noise, the weight of people’s expectations. Building her as an AI meant I could access that version of myself more consistently, even in small, everyday decisions where it’s easiest to shrink.

Maya didn’t change who I am. She made it harder to ignore who I already was. She gives me back my sense of agency.